A priceless piece of sporting history

September 3, 2004

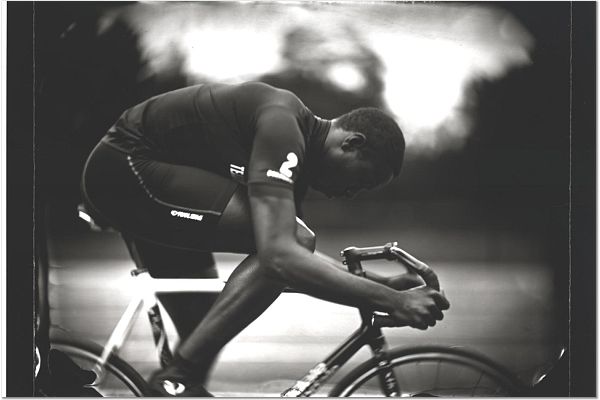

Carrying a legend ... Major Taylor rides the black bike - now owned by Jack Walsh - in Sydney in 1903.

American cyclist Major Taylor, an early victim of racism in sport, once raced at the SCG, writes Steve Meacham.

Jack Walsh, the veteran Australian cycling champion, is pointing out some unusual features on his most prized possession. "Notice the cotterless cranks, the forked crown, the six-day outrigger ..."

Only a fellow cycling enthusiast could possibly understand what he is talking about. But then you don't need to know much about cycling technology to appreciate why the plain old black bike he's pointing at is so precious. You just need to know the story of the man who once rode it.

Few people in Australia now recognize the name Major Taylor. But in America, it is revered.

A decade before Jack Johnson shocked white supremacists by becoming the world's first black heavyweight boxing champion, Major Taylor overcame the same hostilities. When he arrived in Australia in 1902, Taylor was considered one of the most controversial characters in international sport, as only the second black athlete in history (after bantamweight boxer George Dixon) to earn the title world champion.

That's what makes Walsh's "plain old black bike" so remarkable. Though it has been on display virtually unnoticed in Walsh's suburban cycling shop for 15 years, it would excite interest from collectors around the world if he ever put it up for auction. No other cycle ridden by Taylor has ever been identified.

Marshall W. Taylor was born in 1878 in Indiana. His nickname, "Major", came from a soldier's uniform he wore as a 14-year-old when he was hired to perform cycling stunts outside an Indianapolis bike shop. "He was only a little bloke," says Walsh, now 83. "About five foot six [168 centimeters]. A bantamweight, but very powerful."

In 1896 Taylor unofficially broke his first two world records in Indianapolis. Instead of being lauded as a hero, he was banned from the track - too many whites had been offended.

Thereafter he was often refused entry to professional races because of his colour. The southern states wouldn't let him compete at all. Hotels refused to let him stay.

Despite this, by 1898 Taylor held no fewer than seven world records. Even bigots found it difficult to argue in 1899 when he defeated all the white riders to become world one mile (1.6 kilometers) champion in Montreal.

Taylor would have won more events but for his Baptist principles. Like Eric Liddell, the Scottish runner whose story was told in the film Chariots of Fire, Taylor would not race on Sundays.

From 1902 to 1904 he competed annually in Australia, helping to draw crowds of up to 35,000 at the Sydney Cricket Ground (which in those days had a cycling track around it).

In his history of the SCG, Phil Derriman records that in 1903 Taylor, "a deeply religious young man with a reputation for fair play on the track and clean living off it", preached at the Wesley Church in Regent Street, "urging the young men in the congregation to forgo all sports and amusements on Sunday".

His most notorious race came in 1904 when the Australian promoter Hugh D. McIntosh staged his second annual Sydney Thousand at the SCG, offering a staggering £759 to the winner. All the leading American sprinters took part.

Taylor, the favourite who had started up to 165 meters behind some riders under a handicap, finished fourth after appearing to be deliberately boxed in by rivals on the last lap.

After the race an investigation proved that two white American rivals, Floyd MacFarland and Ivor Lawson, had ganged up to prevent Taylor winning in a betting scandal. Of the 11 original starters, seven were banned for up to three years. Taylor was given the runner-up's prize of £110.

The bike Taylor rode at the SCG is the one now on display in Walsh's Punchbowl shop. Walsh discovered the American had given it to a friend in Melbourne when he sailed from Australia in 1904, and it had remained in the family ever since.

Walsh won't disclose how much he paid - "it was a fair bit" - but received confirmation of its cult status recently.

A US film company, making a movie of Taylor's life, twice sent experts from America to inspect the bike. After various tests, they agreed it was definitely Taylor's and offered him $30,000 for it. Walsh refused.

"I'll never sell it. I admire Major Taylor too much. Not just his ability and the way he rode, but the way he lived his life."

Taylor died a pauper in 1932 in Chicago. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

1 comment:

More info about Major Taylor:

http://www.majortaylorassociation.org

The Major Taylor Association is putting up a statue of the champ in Worcester, Mass., and everyone's invited to the dedication on May 21, 2008.

For details see the Events page at www.majortaylorassociation.org.

For Major Taylor books, posters and cycling jerseys, see the Donations page at www.majortaylorassociation.org

-- Lynne Tolman

info@majortaylorassociation.org

Post a Comment